I damn near once scorched my eyeballs out of their sockets. There I was, 32 years old, slicing and dicing jalapenos in half while keeping an eye on the oven; I was making bacon-wrapped jalapeno poppers for my coworkers during another office potluck. I was sweating. I was hungry. I was a dynamo with the kitchen knife. And then I wiped my eyes with my ungloved hands.

It started as an immediate tingling sensation atop and around my eyelids. It’s not so bad, I thought, no big deal! But then the burn began, subtle at first, and then painful, and then I really thought I might go blind as the razorous hot oily remnants seeped into my skull. In my pepper-prepping fervor I had failed to properly wash the little guys and the oil which had been accumulating on my hands from halving dozens of fresh, green jalapenos was now working its way through my optic nerve.

“Milk!” I cried, “give me milk, people!” I stumbled toward the paper towels, doused one in dairy, then lurched back to my desk where I applied milk to my burning corneas using the paper towel as an eyedropper. After 15 minutes, I could see again and the pain began to abate.

Poppers turned out beautifully.

I say all this in lieu of a recent story from the New York Post describing the diminishing spiciness of the gateway pepper, the OG of the Scoville Scale, the once-fiery jalapeno. My favorite burger features jalapenos; my favorite pizza features jalapenos; a sparkling jalapeno ornament adorns our Christmas tree year after year, blessing all who approach its dazzling spiciness.

X and other social media recently erupted when a healthcare writer named Timothy Faust tweeted a link to a 2023 story from D Magazine titled “Here’s Why Jalapeno Peppers Are Less Spicy Than Ever.” Long (and excellent) story short – because most commercial-grade jalapenos go straight to factories for everything from canned peppers to salsas, dressings, and more, consistency in capsaicin – the chemical which creates what most call spicy in their palates (also the active ingredient in pepper spray) – has come to be highly regulated. Consumer products need to be consistent, so over decades, farmers have developed high-efficiency ways of creating predictable peppers for ideal resale.

As generations of jalapeno crops are grown, harvested, and sold, their primary utility – adding spice to just about anything, along with a satisfying crunch – has begun to diminish. Has the fire of store-bought jalapenos gone out?

#Spiceflation Means Larger Peppers and Diminishing Flavor

To combat this – because something similar happened with tomatoes as flavor, crunch, and the subtle nuances of different varieties were slowly being homogenized – there’s a growing call for heirloom jalapenos to be fostered, featured, and sold to return the American palate to what it used to know – the crunch and thrill of an irregularly shaped, green, gleaming jalapeno pepper.

“A lot of peppers are used for processing, which means processors will tend to control the flavor profiles,” said Brad Rubin, Agri-Food Institute sector manager at Wells Fargo, to TFI.

“If processors need to predict heat in products they make, they may choose to require a milder pepper and add the desired level heat to their products. It would be up to farmers to figure out how to produce milder peppers.”

Rubin also pointed out the fact that the larger and more shinier produce tends to go to markets, where their size and shape may well belie their flavor; “the larger the fruit or vegetable, typically flavor suffers,” Rubin added, “and smaller fruit and vegetables tend to have higher flavor concentration.”

Most consumers are familiar with shrinkflation by now – perhaps #spiceflation is the next trend to sweep the market, swapping mild-to-medium spiciness for a more milquetoast flavor, albeit one more applicable to a variety of “I promise this won’t blow your head off” snacks, dips, marinades, and more.

For jalapeno lovers, however, the answer is clear – they’re not supposed to be that spicy to begin with. For many, dumbing and numbing jalapenos down even more renders them lifeless, a poor man’s pepper stripped of flavor and punch.

X Marks the World’s Hottest New Pepper

All is not lost in the world of pepper innovation. In September 2023, Ed Currie bred the world’s hottest pepper:

Pepper X.

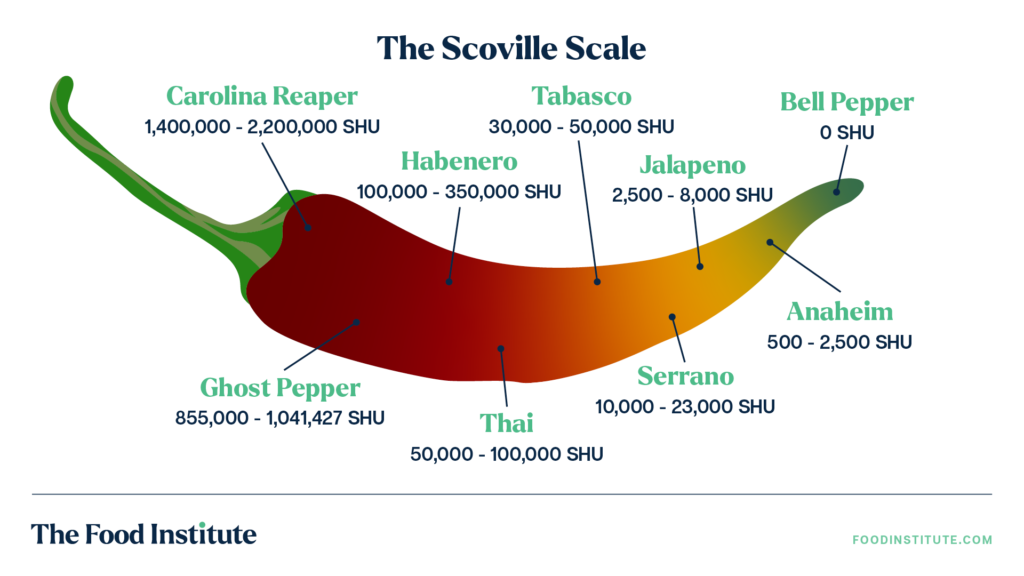

Verified by the Guinness Book of World Records, Pepper X breaks the previous record held by the Carolina Reaper, also bred (and consumed) by Currie. Drumroll, please – the new world record is 2.693 million Scoville heat units (SHUs). The Carolina Reaper is about 1.642 SHUs, so X beats it by quite a magnitude. Described by Currie himself as “an immediate face-punch of heat,” it starts in the mouth and throat, works itself into the gut, and then returns, becoming “an unbearable heat.”

A standard jalapeno registers about 2,500 – 8,000 SHUs. Elongated and forest green, regular jalapenos are easy to consume, easy on the eyes, and look good in almost any application. Pepper X is something else entirely.

The color of a fading bruise, Pepper X is a dull, yellowish grenade covered in irregular horns and bumpy, stippled skin, something less from the garden and more from a nightmare. “It’s just brutal,” Currie said on his YouTube channel of his Frankensteined pepper,” it’s nasty and covered in bumps.”

To witness Pepper X in all its glory (and to sample a clip from Hot Ones, the viral “eat peppers, ask questions” show hosted by Sean Evans), play the video below and try not to sweat.

Thankfully, most consumers will never try Pepper X (much less have any desire to do so). And despite the reported dilution of the jalapeno, the vacuum left in the market will not necessarily be filled by peppers best handled with nuclear gloves, steel tongs, and end-of-life papers signed, sealed, and waiting nearby.

“New pepper varieties have hit the markets like habanero, serrano, etc.,” Rubin continued.

“These peppers are hotter than jalapenos so there may be a perception that jalapenos are milder than they once were.”

What’s more, Currie and other pepperheads’ actions in breeding new peppers has a twofold purpose – to push the limits of the Scoville scale, yes, but also to contribute to medical science. Capsaicin has long been used in skin creams and adhesive patches to help relieve nerve pain.

“When used topically, it initially causes a burning sensation once absorbed, but then it desensitizes the nerves in the region where it is applied, causing an analgesic effect that lasts for a few hours,” noted an article in Big Think.

The article concludes reassuring consumers that capsaicin is generally safe with few side effects besides its noted pain.

Capsaicin, even in small but concentrated amounts, can also be quite thrilling. I’ve had tab-sized slices of the Carolina Reaper. It was bocce ball night, and a friend who had grown them in his backyard brought a few ripe ones wrapped in paper towel, glimmering like stolen rubies nestled in ivory silk. Served on the edge of plastic knives, his instructions were to put the whole knife and tiny tab into your mouth, bite down fully, then withdraw the knife – the bits of Reaper were liable to burn right through your lips.

I came. I saw. I Scovilled, and sweat, and got the shakes, and then it was all over. Later, I had another, embedded among pepperoni pizza to help bear the fiery burden.

“Why do this?” a coworker once asked, “what is the point?”

The point is to ride the rollercoaster, I think, to experience gustatory fireworks, and to simply see it through. I’m glad I’ve tried them. I do not need to try them again.