In 2015 a pair of San Diego-based entrepreneurs – Cassandra Curtis and Ari Raz plotted the launch of a new, high-pressure processing (HPP) baby food brand in refrigerated pouches. The playful name was Once Upon a Farm. It was a bold bet on a future standard of quality in baby food. The pair quickly discovered, though, that the capital needs to insert refrigerated coolers into shelf-stable baby aisles was very high. This fact and the operational complexity of running a refrigerated food brand led them to join forces with John Foraker and other experienced CPG investors in 2017 to help scale the business.

Foraker is best known in the modern food industry for his stewardship of the iconic natural brand – Annie’s, which sold to General Mills in 2014 for $820 million after a brief IPO. Once Upon a Farm was a big leap for him, from shelf-stable to refrigerated, from a broad kids’ brand to a narrow baby/toddler one.

But one other shift would reshape Once Upon a Farm in unexpected ways and not according to the company’s original timeline for growth: the shift from center-store to the high traffic perimeter of America’s supermarkets.

Once Upon a Farm began by attempting to modernize the standards of organic baby food through using HPP processing to preserve the original nutrients and high-quality vegetables and seeds in its blends. This yielded a slightly lower calorie line, and one not skewing heavily to a high sugar applesauce base widespread in baby food. But it also created texture problems that the apple sauce-heavy, added water brands more easily avoided and that lowered initial repeat purchase rates.

With a rapid sequence of Series A and Series B financing rounds in 2017 and 2018 (including S2G Ventures, actress Jennifer Garner, and CAVU), Foraker and the team grew distribution rapidly across most channels, including Walmart, and also launched multiple experimental product lines to accelerate growth.

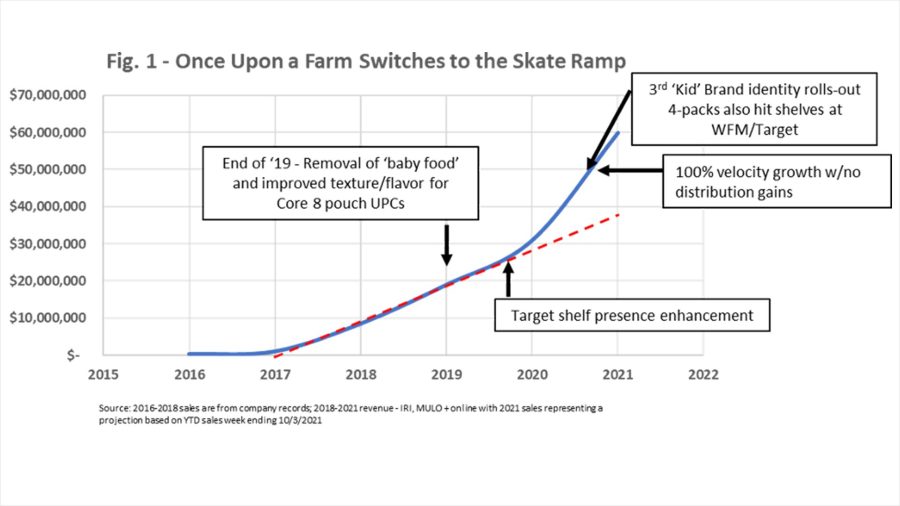

By the Fall of 2019, the brand had reached 18% all commodity volume (ACV) in multi-outlet (MULO),[1] which was around $1M/%ACV on annual basis (see Figure 1), a low ratio compared to most Skate Ramp brands I’ve studied ($3-4M/%ACV is common for this elite tier of brands). The team originally had a twin-aisle approach to growth with baby-food coolers placed in select baby food aisles and pouches sold in America’s dairy cases, next to the kids’ yogurt.

The problem that emerged is a classic one in fast-moving early-stage brands with multiple aisle placements: despite growing velocities in one part of the store (pouches in the yogurt section of dairy), flat velocities in baby food coolers (with upwards of 20 UPCs) combined with underperforming channels featuring poor shelf placement dragged the business into a geometric growth pattern, dependent for growth on a) large distribution gains for a very premium-priced option – omnichannel SRP of $2.49-$2.99- and on b) line extensions.

Yet, the problem was much more serious than divergent velocity trends and inconsistent shelf visibility. By the Fall of 2019, 26% of baby food in America was already premium (i.e. organic for a higher price per unit). [2] The average dollar market share for premium in any given packaged food/beverage category is around 18%. [3] Moreover, as of Fall 2019, baby food in the U.S. was declining on a unit volume basis. [4] America’s birth rate had also hit a wall, especially among upper-middle class women, the core audience for organic baby food historically. And, finally, the annual purchase volume intended for America’s pool of ~300,000 upper-middle class babies was also tiny and declining. [5] Baby food itself was off trend for this lucrative consumer niche, a dietary supplement to fresh produce and breast milk and only culturally relevant for about 9 months (!), which hamstrings repeat purchase as a growth lever.

Meanwhile, Once Upon a Farm’s growing velocities in the dairy aisle started to reveal something else. Moms with infants couldn’t possibly explain the growing Once Upon a Farm pouch sales in the yogurt case, since they are but a fraction of the moms shopping this store section and because half the UPCs driving the growth were a new dairy-free smoothie line not labeled as baby food (and intended for older kids long-term). The other half of the UPCs were the original baby food fruit-and-vegetable pouches (fruits, vegetables and, in a few cases, seeds too!). After texture and flavor improvements had flowed out in 2019, it was now clear that at least eight of the original pouch UPCs were driving the future of the business.

As the team realized they had been trying to grow too much volume in a baby food market trap that didn’t seem ready to relinquish enough market share, they decided to rapidly accelerate their longer-term kids’ strategy and make the shift as quickly as possible. Removing “baby food” from the fruit and vegetable pouches in the dairy case was easy (it would take another year to get a new brand identity to flow out to shelves). By opening themselves up to ALL Moms of kids under 12, the team grew Once Upon a Farm’s core addressable market by at least ten-fold.

One of the most critical realizations for the team was that despite their original intent to launch new lines to reach older kids, they didn’t need to do this at all. Older kids were already eating the dairy-free smoothies and even the fruit and vegetable ‘baby food’ UPCs! The team just needed to double down on what was working and optimize what had become a core 8 UPCs amidst way-too-many.

Instead of adding dozens of new products, the team focused on rebranding for a broader age appeal (the third brand identity historically), improving shelf visibility at key Mom-heavy retailers like Target, AND launching 4-packs, a known tactic to rapidly accelerate snack brands into households with kids (and one evident in the kids’ yogurt section itself).

The result? Despite supply chain issues with packaging and the generalized disruption of the pandemic, Once Upon a Farm doubled revenue in 2021 based on doubling velocity growth. In fact, since the team started measuring SPP velocities, they have grown sell-through rates 10-fold in just three calendar years through a tight, repositioning and by strategically shedding non-incremental lines of business.

Once Upon a Farm’s journey from geometric to exponential growth holds many lessons for early-stage CPG founders selling in retail: 1) don’t get complacent and continually attack your initial assumptions, 2) be open to a strategic pivot well before you need to make it, 3) know your KPIs and track them regularly and 4) once things start to work for a core set of UPCs, double down on them with laser-focused, holistic execution to support velocity growth. And finally, raising $30M early on does not mean your original thesis or playbook was perfect. You must remain humble as you grow. The consumer does not lie. Follow the velocity numbers – always.

Disclaimer: Dr. James Richardson is a paid advisor to Once Upon a Farm; all opinions are his own.

Dr. James Richardson is the founder of Premium Growth Solutions and is the author of Ramping Your Brand.

[1] AC Nielsen Scantrack, xAOC channels, past 52 weeks, week ending Oct 8, 2019; courtesy of Once Upon a Farm

[2] Ibid.

[3] Nutrition Business Journal – 2020 year update, Chart 82 data examining 38 macro-categories in food and beverage

[4] AC Nielsen Consumer Panel, past two years, xAOC channels, week ending 8/10/2019; courtesy of Once Upon a Farm

[5] National Center for Vital Statistics, 2019 courtesy of the CDC; PGS application of upper-middle class slice (8%) based on known high income birth rates (lower than the average woman)