In the face of the coronavirus pandemic, consumers are turning to a staple food: eggs.

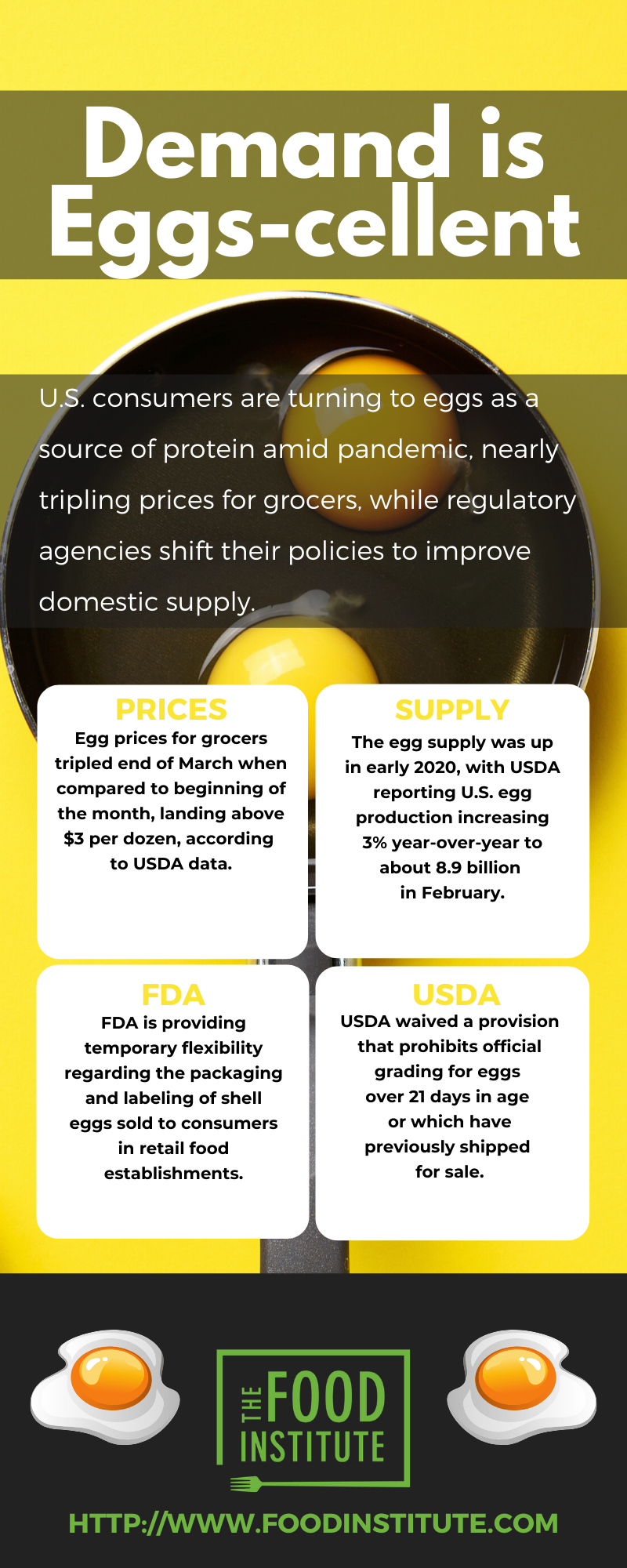

Egg prices for grocers tripled at the end of March when compared to the beginning of the month, landing above $3.00 per dozen, according to USDA data. At the beginning of the month, prices were sitting around 94 centers per dozen, reported The Wall Street Journal (April 6).

Prices on April 3 for extra large eggs delivered to retailers in New York City, the current epicenter of the U.S. pandemic, ranged between $2.87-$2.91, according to USDA. Large-sized eggs ranged $2.85- $2.89 in price, while medium-sized eggs were priced between $1.78-$1.82.

In the Midwest, egg prices for product sold to retailers ranged $2.96-$3.04 on the date for extra large sizes. Large sizes sold between $2.95-$2.97, while medium sizes were in the $2.38-$2.40 range.

The price shift is evident when compared to the beginning of the year, according to Food Institute analysis of USDA data. On Jan. 9 for extra large eggs in New York City, prices ranged $0.78-$0.80; large-sized eggs ranged $0.74-$0.78; and medium-sized eggs $0.67-$0.71. Reported pricing for Midwest eggs on the date ranged $0.77-$0.79 for extra large eggs; $0.75- $0.77 for large eggs; and $0.61-$0.63 for medium eggs.

The dynamic is occurring during a period when other grocery staples, ranging from chickens to cheese to ham, are falling in price. Other food products are seeing overall demand drop as foodservice outlets close; however, supermarkets are ordering eggs at a pace four to six times higher than normal, according to industry officials.

Many retailers anticipate egg supplies will remain tight for the foreseeable future, as it takes four to five months for hens to reach egg-laying age. Anthony Hucker, CEO, Southeastern Grocers, told The Wall Street Journal egg prices were the highest since the 2015 avian influenza scare. Randy Edeker, president, Hy-Vee Inc., said many retailers will simply be forced to absorb a loss on the commodity.

“Costs are going up right now,” Edeker said. “We’re just going to have to lose money on eggs.”

The egg supply was up in early 2020, with USDA reporting U.S. egg production increasing 3% year-over-year to about 8.9 billion in February. The total included about 7.8 billion table eggs, but total egg-laying hens on March 1, 2020 totaled 394 million, down 3% from the same date in 2019.

Egg-type chicks hatched during Feb. 2020 totaled 48.2 million, down 8% from Feb. 2019. Eggs in incubators totaled 49.1 million on March 1, down 8% from a year ago. Domestic placements of egg-type pullet chicks for future hatchery supply flocks by leading breeders totaled 482,00 during February, up 140% from Feb. 2019, indicating supply could recover when those chicks matured.

Meanwhile, shell eggs broken totaled 202 million dozen during February, up 6% from Feb. 2019, but 10% below the 224 million dozen broken during the previous month, according to USDA. During calendar year 2020 through February, shell eggs broken totaled 426 million dozen, up 6% from the comparable period in 2019. To date, cumulative total edible product from eggs broken in 2020 was 552 million-lbs., up 7% from 2019.

To help alleviate the issue, both USDA and FDA are working on ways to provide the U.S. egg industry with flexibilities. As of March 26, USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) immediately waived the provision that prohibits official grading for eggs over 21 days in age or which have previously shipped for sale. The temporary deviation from the voluntary grading regulations were instituted to meet consumer demand by allowing eggs recently shipped to foodservice to be returned to the origin farms for reprocessing, repackaging, and grading for retail distribution.

In addition, AMS allowed a temporary extension of the age restriction for eggs bearing the USDA grade shield from no more than 21 days to 30 days including the date of lay. Roughly 55% of U.S. table eggs are voluntarily graded for quality by AMS, and many egg retailers rely on the USDA grade shield as added assurance to their customers of a consistent, high-quality product, according to the agency.

On April 3, FDA released a guidance document to provide temporary flexibility for the packaging and labeling of shell eggs sold to consumers in retail food establishments.

As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, consumer demand for shell eggs sold at retail has increased. FDA indicated additional shell eggs for consumers are available, but appropriately labeled retail packaging is not offered for all such shell eggs.

Some of the available eggs are in flats, which typically hold 30 eggs and are normally sold to institutions and restaurants and are not labeled. Other available eggs could be placed in cartons, but appropriately labeled cartons are not available. To meet the increased demand for shell eggs in light of the limited availability of retail packaging, FDA provided temporary flexibility regarding certain packaging and labeling requirements for shell eggs.

To facilitate the distribution of shell eggs, FDA will not object to the sale by retail food establishments of shell eggs in cartons or flats without labels, provided that the retail food establishment displays clearly at the point of purchase (for example, on a counter card, sign, tag affixed to the product, or some other appropriate device) the following information: statement of identity; the name and place of business of the manufacturer, packer, or distributor; and safe handling instructions for shell eggs that have not been processed (such as by pasteurization) to destroy salmonella.

Additionally, the agency will provide temporary flexibility provided that if shell eggs from multiple suppliers are offered for sale at the same time and in the same location, it is clear to consumers which point of sale labeling applies to which of the shell eggs offered for sale; the shell eggs are sold by the complete carton or flat; and there are no nutrition claims at the point of purchase for the shell eggs.

The policy was intended to remain in effect only for the duration of the public health emergency. However, as availability of packing and labeling materials improves, FDA encourages industry to resume full labeling as soon as is practical.