If a founder wanted to raise a towering mountain of cash in the 2010s, here was the trick: start anything vaguely related to FoodTech. Anything remotely related to the direct-consumer (DTC) channel proliferated like Palo Verde blossoms in April here in Tucson. Yet, most DTC meal-kit brands simply could not make any money. Retention was fickle. Promotions attracted the barely curious. Most brands that launched back then are long gone.

Hungryroot is one of the survivors. The brand not only pivoted to dramatic success, but it may also soon become the next billion-dollar food brand. This is so rare an achievement that it demands we take a deeper look.

Here’s the trick behind Hungryroot’s success: it pivoted from a narrow CPG business model to a distributor business model with an ultra-limited assortment retail interface. Imagine if a producer just decided to throw up a clever DTC site, and it worked!

Let me explain what Hungryroot did to resolve a long-standing set of intersecting consumer dissatisfactions with “healthy cooking” at home.

A Condensed Timeline of a Master Pivot

2015 – A well-seeded beginning

Hungry Foot is an excellent role model for an adequately seeded food startup, though many newer founders still do not want to accept this. The $2M seed pile bought the team enough time to see if their DTC gluten-free noodle/veggie meal-kit idea was going to work amidst an explosion of DTC meal-kit business startups like Blue Apron, Plated, HelloFresh, Home Chef, Chef’d, Sprigly, Factor, and Freshly.

“When you order from Hungryroot, you get a packaged meal the next day that consists of 70% to 80% vegetables and 20% protein. The base ingredient is vegetable noodles – made from sweet potatoes, radishes, beets, zucchinis, and more – paired with a creative sauce, and served with an optional protein side,” read a press release.

“When you order from Hungryroot, you get a packaged meal the next day that consists of 70% to 80% vegetables and 20% protein. The base ingredient is vegetable noodles – made from sweet potatoes, radishes, beets, zucchinis, and more – paired with a creative sauce, and served with an optional protein side,” read a press release.

The first iteration followed a narrowly framed gluten-free, DTC meal-kit business model, where the brand sourced ingredients and kitted them up in a central facility. But key attributes that would later drive scale were also present. All the original meals were under 500 calories only took seven minutes or less to make. They demanded more preparation than a frozen meal or a box of Mac. But not much more.

Although the business model and offering would change, the core idea that would eventually win was already clear – make above average vegetable consumption super easy and appealing to the non-vegan hard-core majority of us who drift inevitably to meat and carb-heavy meals at home (when we’re tired and even when we know better).

Most educated people today understand that meals packed with fiber (i.e., veggies) will create satiety with fewer calories and help tamp down overeating that leads to steady, inexorable weight gain. We’re educated but easily get tempted into dinner-making habits that are too easy and tasty. And very well-marketed and priced.

2016 – Riding the DTC Meal Hype ~$12M

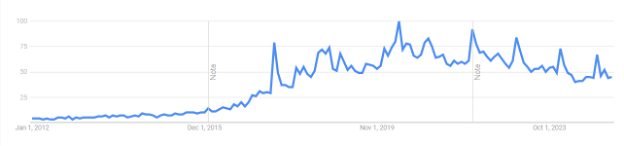

Launching during the era of low consumer acquisition costs (CAC), Hungryroot used seed and Series A and B monies to gain trial rapidly. It also benefited from several billion dollars in investor money flowing into the frothy meal-kit sector long before consumers had become loyal to this or that brand. We were highly promiscuous meal kitters back then. So many direct mail cards offered us 50% off our first box! I remember getting five or more at once some weeks.

Searches for “meal kit” January 2012 – present (Via Google Trends)

During the meal-kit hype ramp up, the Hungryroot team noticed that the business behaved more like a retail outlet than a CPG brand. Evidence? Every time Hungryroot added sides, desserts or other ancillary products, sales grew in direct linear response. Consumers were willing to turn Hungryroot boxes into one of their weekly grocery “trips.”

As the company followed the consumer, they started selling bundles in addition to individual meal kits and other items a la carte.

2017 – Supply Chain Pivot

But the company couldn’t make money. It was also overly attached to simulation-foods in the form of pasta made with this or that vegetable. Trying to package and process everything themselves in a central facility was not a viable path to profit.

Your average premium CPG brand may have 5-20 UPCs when it reaches $100M or so, but Hungryroot was already way past that assortment size. It was moving quickly into retail-levels of assortment without the manufacturing efficiencies of a narrow CPG brand. So, they rebuilt their supply while also harvesting the trove of data a DTC business contains. In the words of one of the founders, “By cutting out the middleman, selling directly to the consumer and being really smart about data, we can leverage customer insights to create new products and to personalize customer experiences.”

In 2017, Hungryroot went from one factory to twelve different suppliers which required a six-month pause in operations. At this point, the company was fortunate to have an oversupplied PE lending market ready to fund a pivot within the hot DTC sector. They raised $7.7M in early 2017 to carry them through the pause. Ceasing operations is not an ideal mode of pivoting, but, when you have the capital to do it and a good reason (i.e. no path to profit), it’s critical to act quickly before you scale to the point of Beyond Meat and can NOT repair the unit economics.

2018-2019 – Hypergrowth with a Profitable Supply Chain

After fixing its supply chain issues and doubling down on its meal-planning AI, the business began to add premium, branded snacks and beverages to expand the frame more clearly to “a box of groceries for the week.” The target proportion of house-branded versus third-party branded items was set at 70/30 (which is roughly what you see now scrolling their item list).

This is the point where the business definitively moved beyond its branded house beginnings (Figures 1 and 3) to a grocery retail model. But Hungryroot had become a very specific, limited assortment online retailer (i.e. 600 or so total items). And it still retains this ultra-tight focus today. From this small list of ingredients, it can create 15,000 meals with its AI meal-planning engine. Consumers won’t see the same meals either, only the same ingredients, further moving the business away from the rigid “meal kit” model.

2020 – Creative Destruction Announced

“Goodbye Meal Kits, Hello Hungryroot” is a post that appeared on the company’s Facebook site in early January before the pandemic. The business had crossed the $100M threshold in 3-4 years after a dramatic pivot and the ability to acquire customers for far less than today’s DTC brands.

Hungryroot was now an online grocer built on top of a distributor business model (i.e., closer to the farm than a traditional retail produce department). But unlike its predecessor Thrive market, it maintained an ultra-limited assortment of items, lower than your average Trader Joe’s (i.e., 3-4,000 items) and ten times less than Thrive Market. And it was not strictly committed to non-GMO and organic. And, of course, it was not just a retailer; it used its app interface to be your weekly meal-planning assistant.

The company’s SmartCart AI learns from customers’ ordering behavior, app usage and consciously entered dietary restrictions/preferences to prefill your cart each week with meals and a few grocery items. This offers consumers semi-intelligent planning and co-shopping. The more you share your preferences and meal feedback, the more it can learn.

This kind of machine learning is not entirely new to the DTC meal-kit world. And it’s not clear if Hungryroot customers think it works better than the suggestion algorithms of competitors. But even if you need to edit the suggested box a bit, it’s quicker than starting from scratch.

2021 – 2024 – Acceleration

The pandemic jacked up the baseline sales of grocery e-commerce, which benefited anyone selling food online. While other meal-kit services got hit by enormous supply chain-related inflation followed by market inflation in 2021 and 2022, Hungryroot’s pricing remains remarkably reasonable due to being closer to the farms with its private-label cooking ingredients. The more it sells its core ingredients, the more profitable it can become, like any produce distributor.

Hungryroot Annual Revenue 2021-2024

Hungryroot’s Competitive Advantages

- Small number of core items (600 in 2023) increases profitability versus the Thrive Market approach to premium ingredient retailing

- Most items are fresh ingredients, mainly vegetables, not branded items – more a produce/meat perimeter shopping experience

- Meals have low prep times

- Meals are vegetable heavy (unlike market leaders Hello Fresh or Home Chef)

- Cheaper supply chain than Thrive Market or Sun Basket – NOT focused on organic, non-GMO or expensive sustainability commitments

Hungryroot undercuts your local produce department by offering fewer items at 30% or less per pound by eliminating the distributors along the way to the supermarket. Hungryroot has assumed the distributor’s position in the value chain while offering DTC meal-planning services as the shopping hook. The high satiety, low-calorie meals require minimal effort. This resolves multiple intersecting trade-offs others in the meal-kit space had not. HelloFresh and Home Chef offer average calorie load, carb-heavy meals for the average American. Blue Apron offers complex meals for the urban foodie. Sun Basket offers organic ingredients only, driving up its serving prices to very high levels.

The Power of NOT Over-Designing

Like similar DTC brands anchored around meal planning, Hungryroot uses a very simple, everyday problem as its behavioral hook – what’s for dinner? But Hungryroot’s answer is incredibly sticky without overdesigning a solution that either a) costs too much, b) involves elaborate kitchen work very few Americans enjoy doing more than once a week or c) resorts to carb-heavy and cheesy solutions to provide fast cooking (e.g. box of macaronic and cheese).

Hungryroot learned from early meal-kit brands that over-designing the offering is financially fatal. Blue Apron, Sunbasket and Thrive Market are great examples of expensive supply chains based on very stringent ingredient standards core to the brand. Novel ingredient supply chains tend to get cheaper only at extreme scale (i.e., if you look at the ingredient portfolio of companies like ADM or Cargill). Anyone who got in early on the organic trend in the 1990s can tell you this. Organic produce still has more demand than supply after decades, keeping prices at a permanent premium above the conventional equivalents (which is why Whole Foods never limited its produce to organic).

With an average annual buy rate of near $1,000, Hungryroot sells to roughly 600,000 households, well under 1% of the available U.S. market. Its price-savvy ability to offer vegetable heavy low-calorie, modern meals for reasonable prices per serving should easily garner another 2-5% of the population over time. The key will be in refining its messaging to make its intersecting outcomes clear and compelling to newcomers.

The Food Institute Podcast

How does one ride the skate ramp in CPG? Dr. James Richardson, author of Ramping Your Brand and owner of Premium Growth Solutions, shares some of the pitfalls many early-stage CPG brands make, and highlights some of the pathways to success.