An investigation coordinated by Europol and involving 31 countries found criminal gangs going into waste disposal sites, seizing expired foods awaiting destruction, relabeling them, and then reintroducing them into the food supply.

Operation Opson XIV uncovered 1.4 million liters of beverages and some 12,700 tons of food valued at an estimated $110.3 million during this year’s investigation, up significantly from last year, due to increased inspections by national authorities.

“One of the main trends identified this year was organized crime groups infiltrating waste disposal companies with the intent to get access to expired food awaiting destruction,” Europol noted. “The criminals then remove the original ‘best before’ or expiration dates using solvents and print new, falsified dates on the packages.”

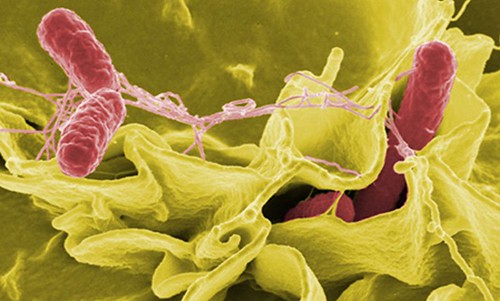

“These relabeled products are then reintroduced into the supply chain. In terms of quality, they may not only be poor but often also pose a health risk, as seen in cases involving canned fish, Europol said.

“As a criminal modus operandi, the practice of relabeling expired food is not entirely new, but its current scale is unprecedented,” Europol noted.

The problem is worldwide.

In the U.S. alone, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 48 million people are sickened by foodborne illnesses each year, but it’s unclear how many of those illnesses are caused by consumption of expired foods.

“Relabeling expired food poses a serious risk to consumer safety and supply chain integrity. Once a label is tampered with, it becomes difficult to verify a product’s true origin or freshness,” Stephen Pavlich, food and beverage labeling executive at Loftware, told The Food Institute.

Edmund McCormick of Cape Crystal Brands told FI the problem with recirculating expired foods is that once they’re past their prime, preservatives and packaging seals begin to degrade, as do nutrients, exposing consumers to bacteria, rancid fats and toxin formation.

“Food manufacturers need to strengthen traceability systems and audit suppliers,” McCormick said.

The Europol investigation found several instances where meat, meat products or seafood wound up in restaurants or were sold to consumers. The foods had been subjected to unhygienic or poor storage conditions, making it unsuitable for sale. Fruits, vegetables and canned goods also were involved. In the case of canned goods, solvents were used to remove expiration dates and new dates were printed.

Some 1.3 billion metric tons of food is wasted annually, equal to about a third of all food produced. Some waste is due to confusion over the meaning of expiration or use-by dates, which are meant to convey when foods begin to lose peak freshness. They still can be safe to eat. The only exception is infant formula, which may not be used after the noted date. Sell-by dates are used by stores to manage inventory.

The situation is confusing and complex, with the most important labels on meat and seafood.

But Meredith Carothers, a USDA food safety specialist, told The New York Times those labels are no guarantee such foods will remain fresh in home refrigerators.

“Once you get it home, better to use it within about one to two days for poultry, or four to five days for raw red meats,” she told the Times.

Next year, California will require labels to specify “best if used by” for quality and “use by” for safety.