It’s said that people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones, especially if those glass walls are covered in leafy greens.

“The CEA [controlled environment agriculture] industry is probably 50 years old,” said Sonia Lo, board director of urban-gro, a CEA architecture, engineering, construction, and consulting firm out of Lafayette, Colorado.

“Dutch glass houses are a well-known, well-proven factor; the vertical farms attracting venture attention are a 10-year phenomenon.”

Perhaps that’s why the space is so competitive. Earlier this summer, CEA industry catalyst AeroFarms filed for bankruptcy. AeroFarms was quick to the 21st-century vertical farming industry, yet despite ongoing growth and retail partnerships for its leafy greens and microgreens, AeroFarms cited “significant industry and capital market headwinds” when it announced it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in Delaware in early June. Chief financial officer Guy Blanchard will take over as acting president, replacing CEO and co-founder David Rosenberg, who will serve as a special advisor to the board.

Lo, a CEA industry veteran, was able to offer some perspective on just what’s going on in the CEA space.

“Compared to distributed solar, this is new infrastructure and we’re still trying to figure out the working models,” she offered. “Venture is the appropriate but very expensive capital to do so; eventually we’ll reach a standard, financeable infrastructure.

“We’re in that transition phase, though, and you expect to see these boom/busts. What’s peculiar is that it’s not software – it’s physical buildings, growing a physical plant and the growing of food, so some of the push-me/pull-you out there is that tech investors get excited about the potential of new technology but the revenues coming in are literally farm revenues – they’re selling produce.”

And produce is hard to profit from, whether it’s at the local farmer’s market or en masse to the millions via retailers and grocers like Amazon, Walmart, Target, Kroger, Albertson’s, and every other mid- and high-footprint grocer in the country. Lo also said there’s a necessary market separation happening right now – a necessary “wheat from the chaff” culling of quick-to-market but ultimately losing endeavors in CEA. “If you have a farm that has no hope of making money, you should rightly not be getting funded,” she said.

The cost of entry is high from both a financial and even environmental perspective. “While CEA provides the advantage of reducing transportation costs by growing food closer to population centers, it’s important to consider its environmental trade-offs,” said Morgan Gold, a farmer at Gold Shaw Farms. “CEA relies on intense energy usage, emits more carbon, and requires a considerable amount of materials to create artificial growing conditions. It’s like trying to mimic nature using lots of electricity and resources, which can have unintended consequences for our planet.

Himanshu Gupta, co-founder and CEO at ClimateAI, says CEA faces many financial, technical, and regulatory questions.

“There’s a high initial investment cost, which can make it challenging for some farmers and entrepreneurs to enter the CEA market,” he said. “Ongoing costs such as energy consumption (from artificial lighting, heating, and cooling) can impact the overall cost-effectiveness of CEA operations.

“Additionally, CEA requires specialized knowledge in agronomy, horticulture, and technology to optimize growing conditions and ensure successful crop cultivation. Acquiring and retaining skilled personnel can be a challenge.” He also noted the lack of standardized practices and regulations in CEA can lead to uncertainty and barriers to scaling CEA operations, especially across international borders.

Just like a backyard or container garden, what you can plant here, in other words, may not necessarily work over there. And that’s just one of many challenges of this wild industry.

CEA Is More Common Than You Think

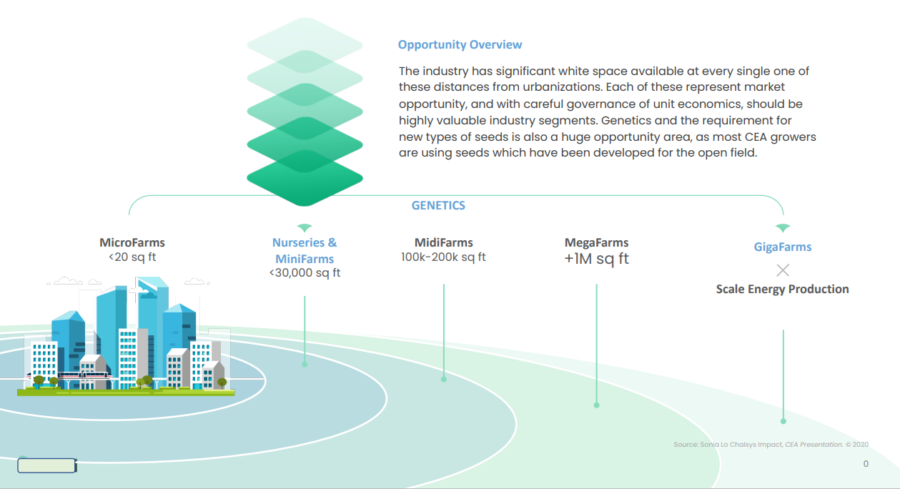

Lo described five categories of CEA farms using the graphic below:

Lo believes there is significant investment opportunity in the nurseries and minifarms (<30,000 sq. ft.) range just removed from city centers, a sweet spot where the infrastructure needed to do CEA well can support the yield and ROI of produce grown at this level. Gigafarms on the far right generally need federal dollars and require the type of space and scale that needs to be legislated and implemented directly into the utilities grid.

Randy Frederick is part of the urban-gro team and has worked with Lo at other companies for almost two decades. A man of many hats and 20+ year consultant to CEA, Frederick said that CEA can really help benefit local communities when done right.

“There’s enough data that shows that local and fresh are key and consumers will spend more to get that. Over 50% of the population is moving toward urban areas and in 10 years it’ll be over 60%, so there are practical reasons why CEA produce makes sense. Local local local and fresh is what CEA can provide.”

Lo added that indoor farming usually won’t provide food security – “They can provide freshness and flavor but they’re not growing wheat or rice. Giga farms have the potential to help create food security but it’s government work and needs to be legislated.”

Lo lays bare the reality of most vertically grown produce. “Leafy greens are the simple choice,” she said. “Years ago, all tomatoes were grown outdoors in the U.S., and now 95% of snacking tomatoes are grown indoors. Tomatoes grown outdoors are larger, which is why you can still get a delicious snacking tomato in the middle of winter. Strawberries are 95% expected to be grown indoors in the next 20 years along with table grapes and melons.”

Frederick said that grapes and peppers also grow well, and that alternate sources of protein with plant-based meat substitutes are part of the future. “We’re in the infancy of that, however, maybe the toddler phase,” he mused.

For Darrin Paschal, chief commercial officer at Growcentia, labor and energy costs are the biggest challenge in CEA today.

“The high infrastructure cost coupled with high labor and utility costs present the most pressing challenges,” he noted. “There are many companies (such as Growcentia) working to help alleviate these struggles.” Paschal said newer technologies that increase the number of crop cycles that can be grown in a season and reducing the amount and frequency of inputs to save time and energy are critical components in this sector, and that “the ability to introduce biostimulants and organic offerings that will provide a positive impact on nutrition content and flavor profiles of controlled environment produce” are some of the most exciting opportunities in CEA today.

The Future of CEA is Unwritten

Lo believes there are two – maybe three – things that may kill us as a species.

“Climate change and diet,” she said, before adding “and possibly AI. The cost and length of time to build the infrastructure to test new ideas is so long that it’s not always useful to do so, compounding the problem. We can’t see around the corner in the market, though, so this food transition, much like the energy and agricultural transitions, might only be in phase 1.5. Many parts of the value chain have to coordinate to produce a perfect juicy steak burger made from plants, for example; it’s being chased by fermentation and mycology-based platforms trying to grow a new protein instead of trying to formulate an animal protein substitute. The first lab-grown burger cost 300,000 euros, and now it’s down to 300 euros, and in the next 10 years it’ll be 30 bucks.”

Lo said that preparation for AI is a must in the CEA sector, and that the learning systems that will be implemented into the next-gen farms will cause exponential change. “Whether that will be for good or bad is hard to say, but a 3,000-sq.-ft. farm that can learn iteratively on an hourly basis will be hard to beat opposed to the traditional outdoor grower farm neighbor who changes once per year.”

“Dovetailing with that is the increase in innovation in robotics,” Frederick added. “Companies are really honing in on how to work with automation/robotics and how to harvest all different aspects of the grow.”

What circled around this conversation at all times was a more existentialist notion – that as a species and an industry, we have failed to address climate change in an actionable enough manner to affect what’s going on outside our Dutch glass-house style infrastructure; thus, we can only look inward (and indoors) to effect change.

“Part of what you see now in CEA is a matter of need,” Frederick said. “CEA does exactly that – it addresses climate change, increases in droughts, and natural conditions that challenge conventional field farming. Seventy percent of the freshwater in the world is used for conventional farming; there has to be a new element to adapt to quickly changing conditions. The good CEA companies do that.”

And like a plant trampled by the dog, what’s gone in this industry is not necessarily destroyed. AeroFarms believes it will emerge from its bankruptcy filing stronger and better poised to address the needs of the market in three, five, 10 years.

“We are fortunate to have existing investors who believe in Aerofarms,” said new president Guy Blanchard to NJBiz. “There is incredible consumer and customer interest for our market-leading microgreens and we are excited to continue to be able to build our business to meet that demand.”

That’s the thing about throwing stones; there’s little they can break that can’t emerge better, stronger, smarter. Where CEA goes is anyone’s guess, but companies like urban-gro, AeroFarms, and a wealth of other standbys and startups are at the forefront of the industry, peeking around that next corner to help feed their families and communities.

The Food Institute Podcast

Following a string of bankruptcies and operational interruptions, the vertical farming industry seems in flux. AeroFarms CMO and co-founder Marc Oshima joined The Food Institute Podcast to discuss the company’s future following its Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing, plus future for prospects for the controlled environment agriculture (CEA) industry as a whole going forward.